Story By Chris Derrett

Photos By Daniel Cernero

He is crazy. Out of his mind. Borderline insane.

They were all saying that; his friends and family tried to rationalize his decision to no avail.

Nobody could figure it out. Why was he putting himself through this? Did he even know what his decision entailed?

Not fully aware of that himself, he strolled through Baylor University’s campus on the first day of class.

His backpack full of supplies matched those of any other student, but his two hearing aids, large glasses and gray hair drew confused expressions as he entered the classroom and took his seat. He looked old enough to be a professor’s father. Or grandfather.

Instead of writing his name on the board and distributing the syllabi, though, he prepared his notebook like everyone else.

When the professor gave the first lecture, he began taking notes. But like everything else about him – his appearance, scholarship situation and life story – his note-taking skills proved a far cry from those of the other students.

The notes came too quickly. His poor handwriting could not keep up.

Finally, after the first week of lectures and assignments, 82-year-old Weldon Bigony realized that college would not be as easy as it was in 1941. It would be a long senior year in Waco.

A bygone era

“It just kind of struck me. I don’t know why it took so long to decide to do it. But it struck me that I never did get that part finished in my life,” Bigony said of his decision to earn his bachelor’s of business administration from Baylor in 2002, 65 years after he first pursued the diploma.

Raised in Big Spring, with five little sisters, Bigony began developing his work ethic in his early years. He retired from cotton picking as a 5-year-old after securing enough money for a red coaster wagon. A paper route, caddying job and stint with the city scraping water deposits off sewage pipes kept him physically fit before he earned an athletic scholarship to Baylor.

During his freshman year in 1938, Bigony ran track and played football and basketball, and he devoted his sophomore and junior campaigns solely to the gridiron. The most notable game of his collegiate career, a 7-7 tie against the then No. 1 ranked Texas Longhorns, remains fresh in his memory today.

For the “student” part of “student-athlete,” Bigony managed a B average. Prior to the spring of 1941, he was on track for a degree in addition to his fourth varsity letter.

Then, at the young age of 21, he began learning the difference between aspirations and reality when the United States entered World War II.

Bigony joined the Naval Air Corps and requested a fighter pilot assignment, ready to take all necessary steps toward earning a seat in the cockpit. His high marks earned him the title of valedictorian at training camp.

Despite Bigony’s excellent grades, the Naval Air Corps denied his request. He would not dogfight with the Axis powers for supremacy in the skies; he would deliver war goods in a multi-engine plane. Trained for service, he reported to Shanghai, China, for the remainder of the war.

A second chance

Six decades later, Bigony was living in Big Spring but wanted to go back to Waco. By that time he had watched his mother return to Texas Tech in her 70s and live to be three months short of 100 years old. He lost his wife in 1996, three years short of their 50th anniversary. Bigony had already retired from a career with Air America and Air Jamaica.

When he applied for readmission to Baylor, he was also a 10-year cancer survivor, defeating it with just a healthy diet and exercise plan and no chemotherapy.

Unlike his fighter pilot dreams, his desire to finish his Baylor degree came to fruition. Only one problem existed.

The call came mid-afternoon, three days before classes began.

“It was Friday when (Bigony) got this phone call from Baylor saying he could come back,” Vicki Peters, Bigony’s daughter, said.

In one weekend, Peters and her husband, James, scrambled to help organize Bigony’s living arrangements. The Peters followed Bigony from Big Spring to Waco, where Bigony temporarily stayed with his cousin, and the Peters took Bigony for his mandatory physical examination and completed his paperwork.

By Monday morning, Bigony was on campus and excited to start. Off campus, the Peters were thinking.

“The next day, (James) looked at me and said, ‘We just can’t leave your dad here. We’re going to have to sell our house and come back (to Waco),’” Peters said.

They explained their plan to move from Big Spring to Waco, but Bigony originally found it unnecessary.

“They were smarter than I was,” Bigony said. “I don’t think I would have made it on my own.”

Eat, sleep, study, repeat

Even with his meals provided and house cleaned by a loving daughter and son-in-law, Bigony had plenty to worry about. For him it was a new era, a new atmosphere and a brand new Baylor.

He soon learned the pace quickened from the last time he attended. Professors demanded much more than Bigony remembered in 1941.

“When I was here the first time, I took a full academic schedule and played sports,” Bigony said. “(In 2002) all I was doing was eating, sleeping and studying because of the workload. How the athletes have time to go practice and keep up in class is amazing.”

Taking notes by hand failed to suffice, as did using a voice recorder in some classes that prohibited them. Bigony finally found students who could reliably provide notes after class.

Taking tests was another process Bigony had to learn for his grades’ sake.

“He would do tests in sequential order. We had to tell him to do the ones he knew, then go back to the hard ones,” Peters said.

Physical aliments also threatened Bigony’s chances.

“At that time he had dizzy spells that would come on, and they would also cause him nausea,” Peters said.

One day Bigony willed himself to finish a class, not wanting to draw attention for getting up and leaving early, and found a restroom afterward. He immediately called the Peters for help.

Sometimes, assistance from those around Bigony went a long way toward his goal.

21st Century Education

A little aid was all Bigony needed to conquer one class that especially frightened him.

At first he thought he could escape computers and ISY 1305, titled Introduction to Information Technology and Processing. Bigony could not even identify a computer’s power button, much less access the Internet and produce a Word document.

For the first semester Bigony had another class substituted for ISY 1305, but it only prolonged the inevitable. Somehow, the technologically removed man would have to master the mouse and keyboard to graduate. A professor’s generosity allowed him to do so.

“It was a little too fast-paced in the class, and so it was easier for me to take it one-on-one with him,” senior lecturer Carolyn Monroe, Bigony’s class instructor, said.

Monroe had never given exclusive instruction to a student before, but she was as determined as Bigony to see him get the credit.

“This professor was so good that she recommended taking me one-on-one. That was outstanding,” Bigony said of Monroe’s extra effort.

They began with the basics, as Bigony would watch and repeat Monroe’s steps on the screen. By the course’s conclusion, “he was surfing the Web with the best of them,” Monroe said.

Bigony appreciated the much-needed help, but he would tell you his greatest source of success came neither from himself nor those around him.

God above all

“(Bigony) would greet me each day with, ‘This is the day that the Lord hath made; let us rejoice and be glad in it,” Monroe said.

God had given him each moment of his 82 years to that point, Bigony believes. With the small amount of the time not devoted to education that year, he did his best to give back to God.

He found a local church, Grace Community Church of Waco, and joined a Life Group. There, nothing else mattered; grades took a backseat to helping one another grow in their relationships with Christ.

Bigony came regardless of impending tests or homework every Sunday for church and Tuesday for fellowship night.

It began with a few church visits and shaking hands on Sunday mornings, morphed into more consistent attendance and finally Bigony became attached to his new family.

“You can call him an elder. His wisdom and ability to lead people is unbelievable, and it’s grown from there. It’s more than a friendship. It’s a family,” church secretary Sue Martin said of her and the church’s relationship with Bigony.

For nearly 90 years full of meaningful pursuits and even more important relationships, Bigony can only thank God.

“The Lord has blessed me with good health,” Bigony said. “I give Him all the credit for it, and I think He’ll continue to see me live a long life.”

The Last Day of School

A year’s worth of work finally came down to one day. Bigony’s heart raced as he focused on one final meeting with the dean. His nerves rendered him oblivious to everything else around him. He did such a good job blocking distractions, that even the audience escaped his attention.

“He couldn’t hear, didn’t know what was going on, and couldn’t see them,” Peters said. “He was focused on the dean walking straight to him, and that’s when he was turned around and we told him, ‘Hey, look…’”

The dean approached him as 10,000 people had risen to applaud Weldon Bigony, class of 2002. He met his professors’ requirements, survived final exams and passed each class. He raised his diploma while his son, who earlier distributed fliers asking the crowd for a standing ovation, and numerous family members proudly watched.

The chapter ended while Bigony’s story continued.

A state champion

“My mother had so many projects that kept her so busy, she had too much to do to die early,” Bigony explained.

His ambition, he continued, follows after that of his mother.

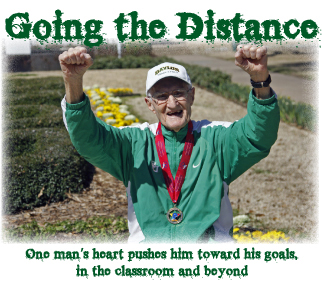

At age 89 Bigony stretches before stepping onto the running surface at Baylor’s Hart-Patterson Track and Field Complex. Hip replacements prevent him from jogging, but they do not stop his training.

He cannot afford to lose a day; the 2010 Texas Senior Games begin in October.

There he hopes to add medals in the 1,500- and 5,000-meter race walk, events in which he has already claimed gold several times at the state level, most recently at the 2008 Texas Senior Games.

In odd-numbered years Bigony competes in the national Senior Games meet, where in 2009 he beat a competitor by eight seconds to earn a 5,000-meter gold.

Between meets, Bigony finds other activities that keep him in Waco.

Still an active member of his church, he works on occasional projects and visits hospitals. A fanatic of Baylor athletics, he follows each sport and can proudly say he attended each home football game and basketball game of the 2009-2010 year.

Bigony delved further into the athletic program upon graduating, taking a training program to prepare for a job with the track team.

“He officiated some of the track meets here at Baylor,” former Baylor director of student-athlete services Don Riley said.

Like many others, Riley formed a friendship with Bigony that grew when Bigony was free of academic restraints.

“He is a delightful person,” Riley said. “He’s very personable and doesn’t act or even look like an 89-year-old person.”

Bigony’s charm also helps him with another, less physical job. He helps develop leads for Coldwell Banker, getting prospective home owners’ contact information and relaying it to the real estate agency.

Between his daily walks and referral associate job, Bigony’s calendar stays full.

Not over till it’s over

Some would say he has done it all. Seen it all. Lived it all. And they could be right.

Bigony rests in his apartment, with a diploma hanging on the wall, family and friends a phone call away, and hopefully another pair of medals to come next fall.

At this point in the day he has already awakened, humbly thanked God for more time in this life and looked for what he can do before the Lord calls him home.

Now he graciously sets aside time to retell a piece of his story to a young, aspiring journalist.

“It’s like a lot of other things. I wouldn’t take for the experience, but I wouldn’t want to do it again,” Bigony said of his senior year.

He doesn’t have to. He finished what he started, and accepting that part of his life any other way would have been crazy. Maybe even insane.