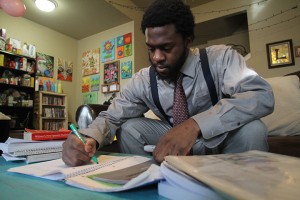

With one brother in medical school and another studying architecture in graduate school, Ogbonna Okonkwo undoubtedly comes from a family of achievers. Okonkwo, however, has decided to take the road less traveled on his path to success.

His birth certificate says Ogbonna Okonkwo, but you can call him Alvin.

“When you see it, you’re going to think it’s Og-bana, but it’s Oh-BWAN-nah. It’s hard to say unless you practice the accent,” said Alvin.

Alvin Ghidozie Okonkwo was born to Chuck and Irene Okonkwo. Although he himself is from Texas, his parents grew up 6,000 miles across the Atlantic Ocean in Nigeria. Therefore, it may be no surprise that Alvin and his three siblings were raised on traditional Nigerian customs and values.

“They say that our home is not this home,” Alvin said. “To them, our home is Nigeria and they want us to know that.”

Alvin describes Nigerian traditions as conservative at least. Most Nigerian families view men as the dominant figures in the household. He adds that parents are strict and stern who try to raise responsible and respectful children whom are taught to be independent at a young age, as it in an important Nigerian custom.

“They were more of the people that were like, ‘you are six years old, you are old enough to go into the kitchen, cook yourself dinner and lock the doors,” Alvin said.

This teaching of independence helps emphasize the Nigerian standard of affection coupled with tough love.

This type of affection seen in many Nigerian households is emphasized through actions and servitude. Alvin recalls that while his mother, a nurse, was at work, he would clean the house making sure it was spotless and that all the chores were completed.

“There’s a deep connection and bond there, but it’s in a different language that most of us today don’t understand,” said Alvin, emphasizing his mother’s point of view that working hard to support and provide for her family was her way of being affectionate.

“We were raised on the principles that nothing is given,” said Alvin. “Nothing is free, so you’re going to work for it.”

For the Okonkwo’s, these principles further sustained the importance of education. Okonkwo’s father began his children’s education at a young age.

When he was four, Alvin says Chuck took him to the library and soon after, began dropping him off at the library. Furthermore, before Alvin went to preschool, Chuck home-schooled him.

It was because of this early start and his parents’ tough stance on education, Alvin rarely made below an A throughout his educational experience. The first time he made a B, Alvin says he was terrified about how his father would react.

Alvin says many Nigerians see education as a way to compete and survive with Americans.

“They felt as immigrants, their children had a slight disadvantage,” Alvin said. “They never wanted us to be labeled as immigrants or Africans, but rather normal American children.”

Alvin says another key reason Nigerian parents hold education to such a high standard is because they feel it controls their child’s future. They generally aspire for their children to go far in education, hoping they become doctors or lawyers.

Kenneth, Alvin’s older brother, is in medical school, while his twin brother Andy is in graduate school for architecture.

Alvin’s little sister, Nina, is currently a freshman at Baylor majoring in neuroscience. Nina is expected to attend medical school and lead a comfortable life as a doctor.

“I want to be a doctor mainly because of my parents’ influence,” said Nina. “Medicine however is interesting to me and I feel I could really enjoy a career in practicing it.”

Although Alvin had no intention of joining two of his sibling in the medical profession, he says law was something he always felt was in his future.

“One day somebody mentioned that I should be a lawyer and it just stuck with me,” Alvin said. “My parents went along with it and pushed me to pursue a law degree, which I ended up not doing.”

After graduating from Baylor in May 2012 with a degree in political science, Alvin still had some sort of a desire to become a lawyer. However after partaking in Teach for America, Alvin began to rethink his plans.

TFA is an organization where college graduates teach in inner-city public schools, hoping to create change in the community through positive guidance.

After teaching kindergartners for a couple of months, Alvin made the decision to no longer pursue a law career. Through a life-altering experience in teaching, Alvin decided to further his career in the field.

Currently, he plans to continue his education in graduate school for educational administration or educational policy.

Alvin says although he is perfectly content with his teaching job, his mother is constantly encouraging him to attend law school. He mentions that many Nigerian parents have set definitions of success that they like to impose upon their children for image purposes.

“In the Nigerian culture, it prestigious for my mom to be able to converse with her friends and say that, yes, her son is a lawyer,” said Alvin. “I just don’t believe in the same things,” adding that he stopped doing so at an early age.

Although the integration of both American and Nigerian customs can sometimes be troublesome, he says this uniqueness is essentially his identity.

Growing up, Alvin identified himself as a rebellious child. As the second oldest, he says he often created the most trouble for his parents.

“I grew up very obstinate, and there’s something in me that’s naturally defiant so I argued a lot.”

In junior high, Alvin began to realize how different his family was from other non-Nigerian families. This created confusion and a desire to stray away from his family’s values and beliefs.

This confusion led to a number of quarrels between he and his parents. So many in fact, his parents reached a point where they stopped getting angry and would simply say, “It’s him again.”

When he arrived at Baylor, Alvin felt as though he was free from his Nigerian roots. After his parents dropped him off and they said their goodbyes, Alvin felt freed.

“When you leave a controlling atmosphere, you feel liberated in a sense,” Alvin said. “But at the same time, you start to really miss the same values of the people who raised you.”

Although Alvin appreciates his Nigerian customs and values, he doesn’t fully embrace them. This includes one very important custom: the custom that includes him marrying a Nigerian woman.

What most would considered to be an All-American blonde hair, blue-eyed white girl, junior Michelle Ratliff, a Baylor track and field athlete from Amarillo is Alvin’s current love interest.

When Alvin first told his parents about Ratliff, they made him feel as though it were a temporary relationship, often referring to her as a new friend instead of a girlfriend.

“They had in their mind a picture of me marrying a Nigerian, possibly from a family they knew,” Alvin said. “It’s a step down from an arranged marriage”

Ratliff describes the first time she met Alvin’s parents as awkward. Alvin said he could see his parents wanted to be cordial and nice, but didn’t know how.

Chuck greeted Ratliff by telling her to come in and sit down, he asked if she wanted anything to eat or drink. When she politely refused, Irene and Chuck viewed her as being disrespectful.

“They weren’t necessarily rude, but it wasn’t a typical greeting that I’m accustomed to,” Ratliff said. “They didn’t really know what to say to me and I didn’t know what to say to them.”

Alvin explains that because they have thick Nigerian accents and are self-conscience on how they talk to others, it is difficult for them to strike up a conversation with anyone who is not Nigerian.

After a year of dating, Ratliff says it is still hard for her to relate to her boyfriend’s parents. She understands that his parents want him to marry a Nigerian, but feels that they should be more accepting.

“They should care more about the happiness of their child rather than their culture,” Ratliff said, adding that although she doesn’t fully understand Nigerian values, she still has respect for them.

Ratliff added that she realizes the hard work Irene and Chuck have put into raising their children.

Alvin, the once rebellious child, is beginning to understand and appreciate his parents’ upbringing.

Now living independently, Alvin and his father see each other as man-to-man rather than father-to-son which ultimately has smoothed their relationship.

Alvin says that when he has children, he will incorporate a few values that his parents taught him. He wants them to be independent and respectful.

“I want to raise my son or daughter on the values that Michelle and I create and come up with together,” Alvin said. “At the same time, I want my children to recognize that they have two grandpas from two very different backgrounds,” adding that for him, cultural awareness is essential.

Written by: Jamie Lim

Photography by: Matt Hellman