Photo courtesy of Lewis Lummer

Show Me A Sign

The first deaf professor at Baylor speaks about growing up deaf and how he advocates for the Deaf community in Waco.

Story By Audrey Patterson

Photos By Gillian Taylor

Imagine a world where people communicate visually through sign language and live without stigma. This world exists in Deaf culture. It’s a place called Eyeth, where life centers on the eye — a society designed around visual communication regardless of hearing status. Deaf culture is rooted in storytelling passed down through generations. Eyeth is a utopian world that has been adapted into books and movies but originated as a story from deaf people.

But on Earth, in an audio-centric society, deaf and hard-of-hearing people know all too well how far the reality of an equal existence is. According to the 2011 American Community Survey, about 3.6% of the United States population is deaf or has severe hearing loss, meaning the average hearing person doesn’t have intentional relationships with a deaf person.

Dr. Lewis Lummer, a senior lecturer of deaf education and American Sign Language at Baylor University, was born deaf and comes from a deaf family of four generations.

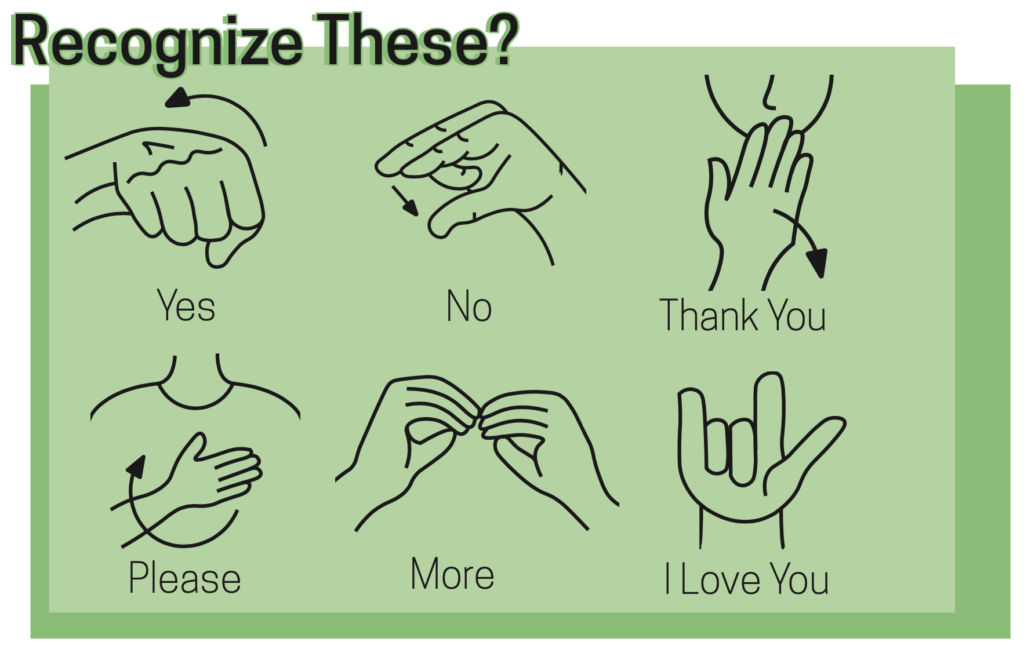

MAKE IT MAKE SENSE: Teaching American Sign Language as the first deaf professor at Baylor, Dr. Lewis Lummer uses his face along with hands to teach students different phrases.

Dr. Lewis Lummer

“We have our barriers, but we do not let that stop us. The term ‘can’t’ is not in our vocabulary because it does not exist … My family always taught me, ‘Don’t let that get in the way of anything you want to do or pursue.’”

Lummer said that growing up, deaf people would tell him all sorts of stories and they were interesting because you never knew if it really happened or if it was made up. Storytelling is cherished among deaf people and Lummer and his family because it passes down experiences, uplifts deaf people and preserves the heritage of their language.

“I grew up using ASL as a natural language,” Lummer said through a sign language interpreter. “I grew up thinking of it as normal because I assumed everybody outside my family used ASL and communicated with their hands. Then I started to notice that other people didn’t know sign language, and I thought that was a little odd.”

Lummer said his parents, who were also deaf, were excited for him to be deaf because they saw him as healthy and normal. He said they appreciated him and accepted him as their whole child immediately.

“We [deaf people] have our barriers, but we do not let that stop us. The term ‘can’t’ is not in our vocabulary because it does not exist. My family always taught me, ‘Don’t let that get in the way of anything you want to do or pursue,’” Lummer said.

Lummer said he is proud to be raised by deaf parents and views them as strong people. His mother immigrated to America from Germany during World War II because of the threat of concentration camps targeting deaf people.

“They taught me not to sit around and just be, but as a result of my life, I was able to persevere. They gave me the teachings of God, and I was able to overcome a lot of obstacles in my life,” Lummer said.

An obstacle for many deaf people is their treatment during primary and secondary education. Accommodations some schools have in place now were originally looked down upon.

Lummer emphasized the Milan Conference of 1880 in Italy, the first international conference of deaf educators, where “they voted and decided that oral education was superior to manual education. They were banning sign language and forcing people to do an oral method of communication.”

The shift in the American education system from verbal to using a combination of sign and verbal in the 1970s heavily influenced Lummer’s experiences at school.

“I did sign language at home, but doing sign language at school was viewed as incorrect, and they wanted us to depend more on the English code,” Lummer said. “So I wrote and read English in class and used ASL outside the classroom. Fast forward to the 1990s, English and American Sign Language were viewed as two separate languages.”

COMMUNICATING FROM AFAR: While earning her own degree and gaining her own life experience, Dr. Lummer’s Ruth, who is also deaf, continues to push for awareness and education surrounding the deaf community. Photo courtesy of Lewis Lummer.

Ruth Lummer, one of Lummer’s three sisters, is also deaf and said via email that she first attended school in a self-contained deaf class because the school didn’t want to publicize deaf students. In 10th grade she transferred to Model Secondary School for the Deaf in Washington D.C., where the school met her educational needs.

Ruth said while there are benefits to not hearing, like an increase of the other senses and the ability to work in noisy environments, there are significant social drawbacks such as stigma and discrimination she experiences.

Lewis said that socially he’s been pitied and viewed as lower and incapable. He said when it comes to “socializing with hearing people, I have to have a hearing perspective embedded in me because if I don’t, then I’m completely lost.”

Lewis said there was one night he left his house keys in his office. He said he tried to contact the police department and spent 45 minutes waiting outside the building by a speaker and a camera. The police spoke over the speaker, but Lewis couldn’t hear them, so eventually, he said a police officer came out to him.

“Even then, when they showed up, they didn’t believe I was an employee there,” Lewis said. “I had to show my badge and business card to prove that, and they were kind of shocked at the fact that I had a doctorate degree just from their body language. It felt disrespectful, and I was offended.”

Negative beliefs about deaf people and discrimination habitually follow Lewis and his sister.

“When I graduated from Gallaudet [University] with my B.S. degree, I applied for teaching positions in the state of Illinois,” Ruth said. “The educational system there won’t hire any deaf teacher who can’t speak with voice. That was the worst discrimination I’ve ever faced.”

Lewis believes etiquette is an important step toward the unstigmatized existence of deaf people as described by Eyeth. Hearing people typically view phrases like “hearing impaired” as a respectful statement, but Lewis said deaf people see it as an insult.

Lewis said using the word “loss” is considered a forbidden word in the eyes of the Deaf community. He said it is an insult “along with terms such as hearing impaired and hearing disabilities. Screaming [internally], making a loud noise and things of that nature stay in our minds all the time. We respect people who are not like us.”

Ruth said hearing people need to understand what it is like to be in her “deaf shoes” to eliminate possible complications in personal relationships.

“Don’t expect me to lip-read and speak with my voice. It is the best practice for hearing people to use ASL to communicate with me or have an ASL interpreter,” Ruth Lummer said.

Rather than remaining silent about discrimination, Ruth and Lewis are advocates and encourage those around them to learn ASL and understand their deaf experience.

Ruth said, “Lewis’ greatest strength is being a great advocate for our deaf education and showing sincere passion for ASL.”

Lewis has lived in Waco for the past two decades and has been an active member and leader in the Deaf community. Lewis said he is an ASL storyteller at the Waco library for children learning sign language around 3 to 17 years old.

“I am able to be there for the children if they have any questions,” Lewis said. “I tell them that it’s a gift that they were born with, and they can improve in that skill if they continue to learn.”

Lewis said there are not a lot of opportunities or support for deaf people in Waco. There are more so in Austin, where there is the only Texas school for the deaf and an increasing population of deaf people.

Lewis said he is working with leaders at the city of Waco to promote better quality of life by helping the city “slowly gain awareness and realize that every deaf individual is unique and a human being. Baylor continues to support and work with the deaf community through us in the Deaf Education, ASL program.”

Lewis is also the first and only deaf professor at Baylor and has lectured for the past 14 years. Lewis said he would love to see Baylor hire more deaf professors, as he wonders if he’ll be the first and last deaf professor to work at Baylor.

“I don’t feel like ASL is viewed as equal here [at Baylor] as compared to other languages that are spoken here, like Spanish, for example,” Lewis said. “When it comes to ASL, it just feels like it’s not accepted. It’s kind of sad because this is a language I’ve used since I was a child, and the language and the deaf people at Baylor are invisible.”

Despite ASL being denied entrance as part of the College of Arts and Sciences core curriculum, Lummer said he hopes to see the campus view ASL as an important human language to use in their daily lives. While the proposal failed with a 12-12 vote, according to “The Baylor Lariat,” many people have tried to incorporate ASL into the Baylor curriculum.

“My vision is to encourage people and for them to gain self-acceptance and know there’s nothing wrong with them,” Lewis said. “Also, just making sure we’re forming connections with ASL and allowing ourselves to be liberated with signing.”

A society using signing like the dream of Eyeth might seem far away. Still, deaf people live every day with communication just as rich, intelligent and personable in a world without sound.